BrainBlog for vFunction by Jason English

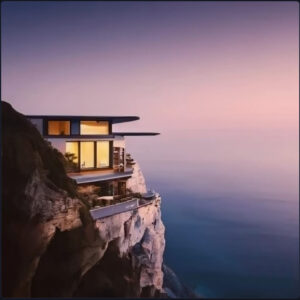

If money were no object, the most idyllic place I could imagine would be a mid-century modern Frank Lloyd Wright style house, designed to fit perfectly into a cliff overlooking the vastness of the ocean, treating residents and guests to breathtaking views.

If I were to acquire such an imaginary bespoke architectural wonder from the 1950’s, I would certainly want to make lots of updates before I could call it a permanent residence. I’d probably need to run all new electrical and plumbing services to bring it up to current city code, and wire the whole house up with a fast internet network, smart lighting and climate controls.

Maybe a new overlook deck, or dig out some space under the foundation to add a garage and a bowling alley. It’s my dream, after all… Then, I wake up as the whole house comes crashing down into the sea.

In some ways, our critical applications are like custom houses built on a cliff—subject to forces of nature like wind, water and erosion—but also susceptible to failure due to architectural drift as changes to the infrastructure impact the resiliency of the entire system.

How can we keep up with our neighbors, if we can’t safely manage the architectural drift that happens throughout an application’s lifecycle?

Learning from pre-modernization architecture

Architectural debt is a unique form of technical debt, because it represents the negative interest accrued due to infrastructure and system design decisions, rather than inefficiencies and bugs in volumes of code. Often, this kind of debt is not a result of the original architecture being bad or flawed in any way.

If you look at my colleague Jason Bloomberg’s previous post on architectural debt, the ‘least possible architecture’ would be the most suitable architecture for adaptation, and leave room for change to naturally occur.

When approaching an existing application architecture it’s useful to do a little prep work before arbitrarily deciding how to break down silos, or morph monoliths into microservices.

Determining design intentions

Why was the original architecture put in place, and what were the key design considerations and customer requirements that led to the software’s initial development?

The concept of ‘intent-based computing’ has largely fallen out of fashion today, but the original business intent of the architecture is worth reviving for this part of the journey.

For instance, scalability may have been an incredibly difficult aspect to achieve 10 or 15 years ago, before elastic cloud infrastructure and microservices were commonly available to the company, so resources or memory may have been allocated exclusively for specific services.

Or perhaps, secure authentication and encryption was once more important than ease of data transfer for a privacy-intensive application, leading to a throttled, slow performing app that can’t keep up with today’s expectations.

If you are in doubt about the value of looking back at the original intentions of software architects in order to figure out what’s next, look no further than the many service interruptions that recently made news at Twitter. When the company cut ties with many of the developers and engineers that were responsible for the original design of the massive social network, user access to their new Spaces feature was denied when it was exposed to peak-traffic events.

Read the entire BrainBlog here.