Imagine for a moment you’re in the woods, trying to climb to the top of a nearby mountain – only you’ve lost your way, and you’re not sure where the mountain is. So you get the bright idea: simply walk uphill until you can’t walk uphill any more. At that point you’ll be at the top of the mountain, right?

The answer, of course, is perhaps, but probably not – and in any case, the strategy of always walking uphill is an unquestionably poor technique for finding your way to the top of a mountain, given the unpredictable nature of the terrain. After all, this strategy will simply take you to the top of a nearby hill. Only if you’re exceptionally lucky will that hill end up being the mountain you’re looking for.

This hill-climbing story illustrates the problem of local optima: any optimization strategy that focuses on improving the current situation may not lead to the best solution. So, how do you find the best solution? Well, it depends. Perhaps you can see the mountain from where you are, but perhaps not. Maybe you simply have to RTFM (read the frickin’ map), assuming you have one, and you can identify your current location. Or perhaps you should set off in a random direction for a random amount of time, see where you end up, and then try going uphill – repeating as often as necessary. Eventually you’re bound to hit upon the mountain, right? Bottom line: there is no straightforward answer.

This hill-climbing story illustrates the problem of local optima: any optimization strategy that focuses on improving the current situation may not lead to the best solution. So, how do you find the best solution? Well, it depends. Perhaps you can see the mountain from where you are, but perhaps not. Maybe you simply have to RTFM (read the frickin’ map), assuming you have one, and you can identify your current location. Or perhaps you should set off in a random direction for a random amount of time, see where you end up, and then try going uphill – repeating as often as necessary. Eventually you’re bound to hit upon the mountain, right? Bottom line: there is no straightforward answer.

The reason this Cortex is spending time climbing mountains is because the local optima problem affects most Digital Transformation initiatives, since the majority of such initiatives are centered on some kind of optimization activity: optimize the customer experience, or optimize the integration of Web and mobile, or optimize the organization’s use of social media, etc.

If you set a goal based upon starting where you are today and heading in a direction that will improve the current situation, you will likely reach a local optimum. But it probably won’t be the true optimal strategy, because, of course, some competitor will end up beating you to the top of that mountain – a mountain you may not have even known about until it’s too late.

Nevertheless, managers love optimization strategies, because they lead to positive business outcomes, and positive business outcomes lead to cash bonuses. And after all, labeling such optimizations as Digital Transformations is generally accurate, as you are using digital technologies to change your business somehow. But we’re still missing a big part of the transformation picture: disruption.

Disruptions shake up the status quo in some unpredictable direction, much like the random walk approach to finding the mountain peak. They can help you avoid the problem of local optima, but even so, there’s no telling if they will take you any closer to your goal. The challenge for Digital Transformation initiatives, therefore, is to leverage – or even introduce – disruptions in a way that will actually help you find that highest mountaintop.

But disruptions are inherently unpredictable and risky. External disruptions – sudden changes in the marketplace, geopolitical environment, available technology, etc. can occur at any time, and even internal disruptions, including reorganizations, changing management policies, new management, etc., can lead to unpredictable results. What’s a risk-adverse manager to do?

Intuition tells us that disruptive transformations are potentially much more likely to help us achieve our strategic goals than optimization transformations, even though they appear to be much higher risk. Do we stick to optimizations, comfortable in the business outcomes we can achieve, even though we may miss the mountaintop? Or do we place a bet on a disruptive transformation, even though it feels like a plunge into chaos? Perhaps we have no choice, as an external disruption may force us to take the riskier path. How do we manage our Digital Transformation then?

Enter Complex Systems Theory

Some background: Complex Adaptive Systems are self-organizing systems of systems that exhibit emergent properties, which are properties of the system as a whole that aren’t properties of the component subsystems. The central principle to all of Intellyx’s research is that the enterprise is a complex system consisting of people and technology subsystems, and business agility is an emergent property of the organization as complex system. The challenge of Agile Architecture, therefore, is influencing people and technology in such a way as to achieve business agility, rather than the chaotic behavior that large organizations typically exhibit.

Many natural phenomena can be explained in terms of emergent behavior, from the construction of beehives to the effects of DNA. The analogue in nature we’ll use in this Cortex is the power of natural selection that enables species to adapt to changing environments.

As complex systems consist of component systems and their relationships, we can think of such systems as networks. In the case of evolution, the components are individual creatures in an ecosystem; for us, the components are people and technology systems. Sometimes the connections (or edges, in network-speak) between components are tight, for example, within family groups, or loose, as they might be between different groups. In the case of an enterprise, tight connections between people include hierarchical reporting structures, behaviors that result from formal governance policies, etc., while loose connections would refer to interactions between people in different teams or in different parts of an organization. Similarly, tight connections between technology systems would include traditional integrations between systems, while loose connections indicate interactions between loosely coupled systems that are architected properly for inherent flexibility.

Shifting a system from high connectivity to low connectivity increases evolutionary change. Furthermore, disruptions also lead to increasing rates of evolutionary change, in particular when the system exhibits low connectivity. Such change leads to adaptation to the disruptions in the environment, so combining low connectivity with disruptions leads to periods of rapid innovation and adaptation. However, when a system retains its high connectivity during periods of disruption, that system is less likely to evolve, and thus won’t adapt to the change. Extinction, of course, is the eventual result.

The lessons here for enterprises seeking Digital Transformation are straightforward. In order to foster high levels of innovation that lead to adaptation to both internal and external disruption (in other words, behavior that gets you to the top of the mountain), you must foster an organization with low connectivity and furthermore, give them flexible, loosely coupled technology tools. In such environments, teams have the leeway to self-organize, and their innate creativity will foster innovations that will lead over time to the best solutions. And the role of management in this process? Give people the right tools and get out of their way.

The Adaptive Flexibility Matrix

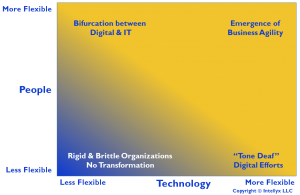

For our Digital Transformation efforts to be successful at achieving our strategic goals (as opposed to optimizing for short-term business outcomes), we must embrace disruption, loosen the connections between people and take steps to make our technology loosely-coupled and flexible. Such transformation is a tall order to be sure, and many organizations seeking it drop the ball in one way or another, as shown in the chart below.

Adaptive Flexibility in Digital Transformation Initiatives (click for larger version)

The chart above maps both technology and people in an organization from less flexible to more flexible. If neither are flexible, of course, then transformation is impossible, and you’re stuck in the lower left corner.

One mistake companies make as they try to get out of this corner is to focus on building or buying more flexible technology, without going through the more difficult cultural and organizational shifts that lead to more flexible people. Such companies move across the bottom of the chart from left to right, and end up with “tone deaf” digital efforts – yes, they may have mobile interfaces and social media, but perhaps their mobile technology isn’t responsive, their social media strategy puts off or angers customers, or they drop the ball on the human side of Digital Transformation in some other way.

Another common mistake is to undergo a digital initiative in the face of inflexible technology: moving from lower left to upper left on the chart. In these organizations the digital team leaves the recalcitrant tech behind, separating the digital efforts from traditional IT – which leads to dangerous pitfalls for any digital effort.

The reason why successful Digital Transformation initiatives are so deceptively difficult is that organizations must change along both axes at once in order to achieve the upper right hand corner, which has all the elements the complex system of the enterprise requires to build innovative, self-organizing teams that can both respond to disruption and leverage it for competitive advantage – in other words, achieve the business agility that drives all true transformation.

The Intellyx Take

If you understand how with the proper initial parameters, complex systems can lead to high levels of adaptive innovation in times of increased disruption, then the argument in this Cortex makes complete sense. However, it is deeply counterintuitive when you place it into the context of traditional management approaches.

Unfortunately, much of the Digital Transformation thought leadership available today comes from management consultants, who spend much of their time advising executives. “Digital maturity requires strong leadership to drive change!” trumpets MIT Sloan Review. “Successful [Digital Transformation] does not happen bottom up. It must be driven from the top!” exclaims Capgemini (exclamation points added, but boldface was all theirs). Such consultants have that perspective, of course, because they have to present a story executives are comfortable with.

In contrast, this Cortex should make traditionally-minded executives (namely, the ones who purchase management consulting) extraordinarily uncomfortable. Stop managing hierarchically. Instead, spin off autonomous, self-organizing teams. Don’t fear disruption. Instead, embrace and drive disruption. Change reporting structures. Move people around. Rethink governance. Revamp HR policies and procedures. Get rid of all the scar tissue in the organization that is getting in the way of innovation. Let people self-organize and let them figure out how to adapt to disruption on their own. The leadership we really need is likely to be quite different than the leadership the consultants are talking about.

To old guard executives, this approach sounds like a recipe for chaos. However, complex systems theory has a whole chapter on chaos as well, and the old guard has it backwards. In fact, chaos describes the status quo at most large enterprises – bureaucracy, empire building, the absence of a single source of truth, inflexible legacy technology, and rigid processes that stifle the best and brightest. Instead, this Agile Architecture approach leads to emergence – business agility in the face of any disruption, self-organization that leads to adaptation and drives innovation. Isn’t that the Digital Transformation you’re really looking for?

Image credit: ThenAndAgain

Fully agree. In the section about spontaneous networks in the decision process of a book about agility in the GRC process, we wrote: ‘Supporting collaboration in a complex and dynamic environment is about supporting spontaneity. As we know, ‘Spontaneity is anathema to business process flows because it requires the ability to be fully adaptive to a situation, especially the unforeseen.’ In this book we compare leadership with directing a Jazz ensemble.

Source: Playing Jazz in the GRC Club

Website: http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/thei_geurts

Jason, I totally agree with you; very bright ideas, and impressive style.

It looks to me that you are familiar with optimization theory, and use an appropriate optimization terminology (uphill, local minima) as an allegory to describe a business behavior. But in fact formal optimization algorithms are not used, and Big Data is used not for optimization, but to generate innovative insights which are able to trigger further business improvement.

What would you say if we could use large datasets, generated by a business, as an optimization environment, and apply optimization algorithms to find optimal business solutions? In this case we don’t have to rely on insights, but have business solutions found automatically.