The battle over bimodal IT is heating up. Now that there’s a reasonably broad consensus that Gartner’s advice about bimodal IT is deeply flawed – consensus everywhere except perhaps at Gartner – various ideas are springing up to fill the void.

The bimodal problem, of course, is well understood. ‘Traditional’ or ‘slow’ IT uses hidebound, laborious processes that would only get in the way of ‘fast’ or ‘agile’ digital efforts. The result: incoherent IT strategies and shadow IT struggles that lead to dispersed, redundant, and risky technology choices across the organization.

The battle, however, isn’t over the problem. It’s over what we should do about it. Perhaps we should add a third mode?

That’s the opinion of Simon Wardley, a long time thought leader, business strategist, and all-around curmudgeon who has been beating the Value Chain Mapping (VCM) drum for many years. He and I are of similar mind with respect to Gartner’s bimodal IT advice – so much so that I quoted him in my recent Forbes article, Bimodal IT: Gartner’s Recipe for Disaster.

Where our opinions diverge, however, is how to fix the problem. Following the precepts of VCM, Wardley introduces an intermediate mode, leading to what he calls trimodal IT. From my reading of Wardley, however, I believe that applying his trimodal approach to the challenge of bimodal IT is improperly thought out.

It’s not that his ideas aren’t sound, but rather that how he applies them to this particular problem leads to unintentional misunderstandings and in the end, incorrect conclusions. It’s time to clear things up.

My Interpretation of Wardley’s Value Chain Mapping

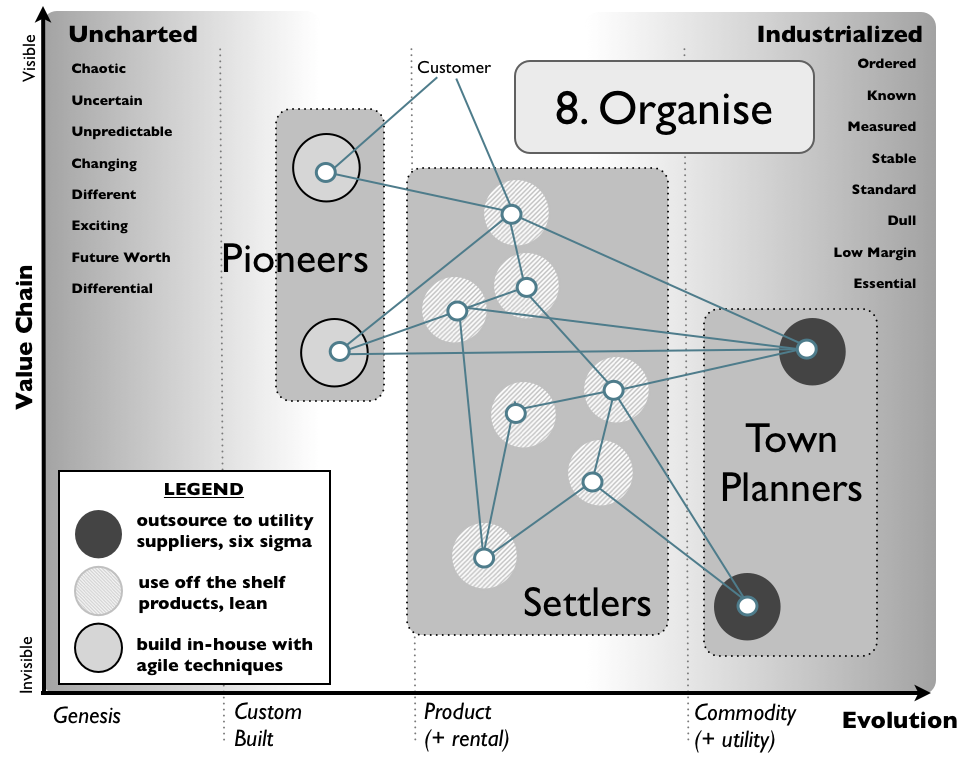

Value Chain Mapping (VCM) is an approach to creating a business strategy that focuses on customer needs and the steps necessary to meet those needs, what Wardley calls a value chain. As the VCM for an organization matures, the activities in each value chain coalesce into three main groups of people, as shown in Wardley’s illustration below.

The organization step in Value Chain Mapping (Source: Simon Wardley)

In the diagram above, the ‘pioneers’ are driving innovation, the ‘settlers’ take the resulting innovations and turn them into products, and then the ‘town planners’ take those products and scale up production, thus driving profitability for the enterprise.

As an approach to business strategy, VCM makes plenty of sense. Enterprises from big pharmas to auto manufacturers have been following this recipe for decades in one form or another, after all. But does it solve our bimodal IT problem?

Wardley thinks it does. He sees bimodal IT as an application of the chart above, only missing the middle, ‘settlers’ section – thus casting the ‘fast,’ digital efforts as pioneers and ‘slow,’ traditional IT as ‘town planners.’

From Wardley’s blog: “The problem with bimodal (e.g. pioneers and town planners) is it lacks the middle component (the settlers) which performs an essential function in ensuring that work is taken from the pioneers and turned into mature products before the town planners can turn this into industrialised commodities or utility services. Without this middle component then yes you cover the two extremes (e.g. agile vs six sigma) but new things built never progress or evolve. You have nothing managing the ‘flow’ from one extreme to another.”

The Problem with Trimodal IT

The problem with the bimodal IT pattern, however, isn’t the need for an intermediary mode – the entire question is what we should do with slow IT. Fundamentally, this problem isn’t a VCM problem at all.

You can see why Wardley made this correspondence between bimodal IT and VCM. The ‘pioneers’ are the innovators, fast-moving and chaotic. If you’re building software than these folks will likely use Agile/DevOps approaches. Sounds a lot like fast mode IT for sure.

The problem, however, is with the slow mode. The trimodal pattern recasts slow IT as ‘town planning,’ which is a poor fit at best.

If you applied the VCM model to IT, and the ‘town planners’ represented traditional IT run in traditional, slow, waterfall ways, that would be different. But in reality VCM characterizes the ‘town planner’ phase with commodity, utility services.

Just one problem: traditional, slow IT doesn’t deliver commodity services as a utility. In the IT context, IT reaches ‘town planning’ when it’s using the cloud. And we all know the cloud is quite different, both technologically and strategically, from traditional, slow IT.

In other words, VCM is a very good fit for describing the evolution of the maturity of IT services generally. In the early days all we had were bespoke applications running on manually configured infrastructure (‘pioneers’). Over time vendors productized the enterprise apps and we developed standard processes like ITIL for dealing with the gear (‘settlers’). Eventually we externalized and abstracted the infrastructure so that we could deliver it as well as software on demand as a service (‘town planners’).

If we bring this vision of VCM to enterprises struggling with bimodal IT, then the cloud bits of what they are doing are the ‘town planning,’ and the pioneers and settlers use the cloud as needed for their own tasks. In other words, ‘town planning’ doesn’t correspond to slow-mode IT at all.

Wardley’s trimodal IT model, therefore, makes perfect sense in the appropriate context – but applying the ‘town planners’ category to traditional IT is a complete mischaracterization. Instead, if we compare trimodal to bimodal’s ‘fast’ and ‘slow,’ the entire trimodal value chain – pioneers, settlers, and town planners – should all fit into ‘fast.’

Industrialization of IT: Flexible or Not?

One of the reasons why the third mode of trimodal is so confusing centers on the choice of terminology.

Note that in the diagram above, Wardley puts the town planners in the ‘industrialized’ band. ‘Industrialization’ brings to mind, say, Henry Ford’s assembly line. Certainly, we could say that Ford’s innovation was ordered, known, measured, stable, standard, dull, low margin, and essential – all characteristics of industrialization from Wardley’s Value Chain in the diagram above.

In retrospect, however, Ford’s market dominance was short-lived, because his business strategy wasn’t flexible enough. His “any color as long as it’s black” philosophy simply didn’t meet customer needs on a long-term basis, and as a result, Ford ceded leadership in the automobile market to General Motors – who not only offered other colors, but also a diversity of brands and perhaps the most important innovation of all, the model year.

When we talk about the industrialization of IT, therefore, do we mean so slow and inflexible that we’ll increasingly struggle to meet customer needs over time? Given that the term generally has a positive connotation, this negative interpretation would not align with most people’s meaning of the word – and yet, such a meaning is in fact what we mean by the bimodal slow-mode.

There is, in fact, no clear definition of the industrialization of IT. Gartner, predictably, excludes any notion of flexibility from its definition: “The standardization of IT services through predesigned and preconfigured solutions that are highly automated and repeatable, scalable and reliable, and meet the needs of many organizations.”

The reason Gartner’s definition above is so predictably inflexible is that it aligns with their ‘slow IT’ worldview. The best we can expect from slow IT, according to Garner, are standardized, repeatable solutions – but flexibility? Perish the thought! If you have a lot of inflexible legacy gear and you’re looking for an excuse to keep it around, then Gartner’s advice will likely appeal to you.

In contrast, take a look at CapGemini’s definition of industrialized IT, which includes new operational models like globalization, offshoring and IT shared service centers, new engagement models including cloud computing, and new technologies that leverage virtualization. Their definition also includes organizational changes like improved financial transparency and the shaping of new IT governance models.

In CapGemini’s worldview, therefore, there’s little room for inflexible legacy in industrialized IT. If you have such gear, then industrializing your IT according to this definition will take plenty of time and money to be sure, and clearly the good folks at CapGemini would be only too happy to help. That being said, CapGemini is unquestionably on the right track here.

The challenge with bimodal IT, after all, isn’t aligning fast with slow. It’s fixing slow. That doesn’t mean simply making it fast, an impractical straw man which underlies the bimodal canard that Gartner has been peddling. But it also doesn’t mean commoditizing slow and turning it into a service, either, as that approach would never support the agility goals of the enterprise.

The Intellyx Take

Any IT strategy that recommends transforming into an efficient but inflexible technology organization simply doesn’t make sense in today’s digital world, as companies strive to become software-driven enterprises.

Value Chain Mapping may be useful for improving business strategies for enterprises looking to scale their product offerings, but characterizing bimodal IT as nothing but trimodal IT without the settlers directs the focus away from the real issue, which is how to properly transform traditional IT organizations to support the enterprise’s agility requirements.

When it comes to such transformative modernization, CIOs have been dragging their heels for years. It’s too expensive or too difficult, they say. It’s too risky. And perhaps it was.

At some point, however, the risk of not transforming traditional IT surpasses the risks inherent in biting the bullet and moving forward with such transformation. Across the globe, today’s enterprises are hitting that critical inflection point now, if they haven’t already.

Making the right decision at the right time about transformative modernization will be a company-saving or company-destroying decision – and remember, no enterprise is too big to fail. Choose wisely.

Intellyx advises companies on their digital transformation initiatives and helps vendors communicate their agility stories. As of the time of writing, none of the organizations mentioned in this article are Intellyx customers.

I think you’re grossly mischaracterizing Simon Wardley’s model. He’s not associating Pioneers, Settlers, or Town Planners as “fast, medium, and slow speed”. He saying each camp is important, and each camp has its own form of innovation and culture associated. In other words, there’s a VALUE PROPOSITION for each mode. When you’re sitting on a cash cow (an IT system that’s doing what it was designed to do and driving revenue), you don’t want the same people who “reimagine what the customer wants across your entire business portfolio” handling the care and feeding of that cash cow — the risk/reward isn’t there. New ideas are inherently more prone to failure than ones that are already working. Don’t believe me? What’s the survival rate of the average new restaurant? One year? So, if you boil down Wardley’s ideas: you want a meaningful way of categorizing ideas, what type of team works on each kind, a way of identifying where that idea happens to fall (Wardley’s mapping concept) on the diffusion of innovation curve so that you’re not wasting your time doing something that’s already been done better by someone else, AND, you want a way to keep coming back to that map to inform yourself about what you should be doing about technical debt. THAT is what’s missing in the Gartner “fast / slow” nonsense. It’s not about fast and slow (systems of engagement and systems of record). It’s about whether you’re ACTUALLY innovating in the back office systems or not (which might just be taking advantage of commoditized offerings), and the biggest issue there has been that nobody uses anything like Wardley’s maps to help them understand that they’re WAY past the point where they should have purchased a commoditized offering. That’s not to say that this has *never* happened however. Shops have been outsourcing their z/OS operations and doing colos for decades (IaaS cloud is just the new model of doing that. Wardley didn’t have a lot of experience with z/OS, so he used cloud as an example of what shops should be doing if they were built on on-prem x86 infrastructure.)

I also don’t agree with your categorization of each camp as they relate to technology. You’ve asserted that Town Planners do waterfall slowly corrected with Lean Six Sigma, and Pioneers do Agile/XP. I don’t think he’d agree with that at all. I think he’d be more inclined to say that Town Planners do some form of Agile that has a more rigid Lean component (like Agile/Scrum + Toyota TPS), that Settlers would apply the various forms of Agile that still have a component of experimentation (like Agile+XP), and that Pioneers are out figuring out how to do work in a way that gets them a minimum viable product without all the rigor of Agile+XP. For example, we seriously need to question whether the rigor of TDD or a CI/CD pipeline makes sense when you haven’t even established whether a product is viable yet.

Anyway, I think you owe it to Wardley to discuss your interpretation of his valuable insights with him before blasting it out on your site as if you have some special awareness that he didn’t. You’re just mischaracterizing what he’s saying, and then reacting to your own strawman.