It may not get the headlines, but ad fraud is one of the most lucrative forms of cybercrime.

Online advertising is the economic engine that drives the vast majority of online content and social media – thus representing a substantial part of the day for billions of people on this planet.

The mechanisms behind online advertising are complicated – and complexity breeds opportunity for the criminal. Each ad represents an elaborate dance involving the end-user, the content publisher, the advertiser, and the advertising service bureau that handles the mechanics of each online ad.

This complexity expands the threat surface, giving criminals many openings – and thus raises the bar for advertisers who must fight increasingly sophisticated ad fraud.

The Multifaceted Nature of Ad Fraud

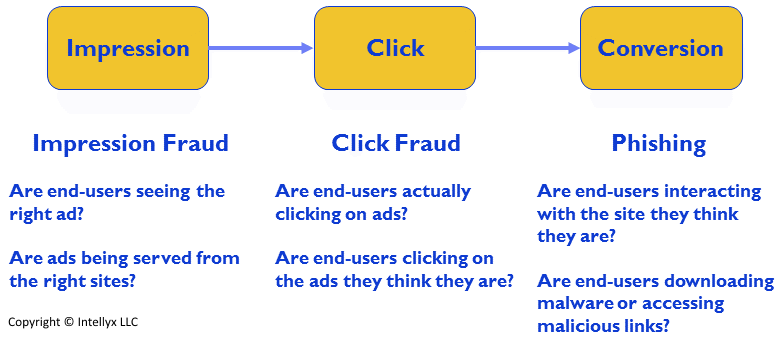

In fact, each step in the online ad process is a potential point of compromise, as the following illustration shows.

Sometimes the criminal is working on behalf of a publisher, attempting to run up the bill for real ads in order to fleece the advertiser. In other cases, the bad guy is interfering with the advertising service bureau in order to divert illicit funds, independent of the publisher.

Impression fraud can serve either purpose. If the advertiser is paying for a certain number of impressions, then the criminal will artificially inflate those numbers by fooling the system into thinking real people are seeing the ads, even though they are not.

In other cases, the malefactor is illicitly forcing ads to run on the wrong sites – typically high-traffic sites (like porn sites) that have nothing to do with the advertised product. In this case, the criminal must also game the system so that it appears to the ad service bureau like the ads are appearing on the proper sites, even though they are not.

The most common type of ad fraud, however, is click fraud. A click – an instance of an end-user clicking an ad – is far more valuable to the advertiser than a mere impression. To perpetrate the fraud, the criminal leverages malware that mimics user clicks in such a way that the clicks appear to come from real end-users. The most common approach to this deception is via bots – malware on end-user’s computers or other devices that is able to invisibly execute fake clicks.

Additional tricks up the criminals’ sleeve that depend upon ad fraud extend to other types of hacking. For example, fake ads can lead to phishing attacks, tricking the end-user into downloading malware or entering personal information on a fake website.

The First Step to Fighting Ad Fraud: Understanding the Problem

Ad fraud is a cat-and-mouse game, where the criminals up their game every time their victims mount a defense. Fake impressions and fake clicks have to look real for the scam to work. Similarly, phishing depends upon deception as well.

For this reason, the most important technique in the bad guys’ hands is obfuscation. The very best con, of course, is the one where the victim doesn’t even know they’ve been compromised.

The first step in fighting ad fraud, therefore, is visibility – not simply in broad strokes, but at a granular level. Defending against ad fraud requires an understanding of what end-users see and do – both individually and in aggregate.

Real user monitoring (RUM) is part of this story. RUM tools typically insert a JavaScript snippet into the pages end-users load in order to track their behavior as they interact with a site. RUM tools can thus provide visibility into fake impressions and fake clicks as long as end-users actually interact with some aspect of the fraud, say when somebody sees a fake ad.

However, RUM is unable to report upon behavior that end-users don’t experience, like ads they don’t see and clicks they don’t make themselves. As a result, ad fraud behavior often goes undetected.

The missing piece of this puzzle: an IP proxy network, like the one from Luminati. An IP proxy network goes one step further than RUM, enabling the security analyst to take actions from the point of view of special software running the devices of real end-users (who have opted in, of course).

IP proxy networks can thus uncover fraudulent patterns that security analysts cannot uncover any other way. For example, to detect impression or click fraud, the analyst can view a particular ad from the vantage point of hundreds of end-users that fall within the particular demographic that the advertiser is trying to reach.

The analyst can then compare the patterns of ad impressions or clicks from the perspective of real people on the IP proxy network with the report on impressions or clicks that the ad service bureau is providing. If they don’t match statistically, then the analyst has determined that impression fraud has occurred.

Furthermore, because all the test traffic originated with real end-users, there is no way for the fraudster to detect these countermeasures, and thus they cannot cover their tracks as they would with more direct anti-fraud techniques.

IP proxy networks are also an important tool for fighting phishing that is the result of ad fraud. IP proxy network traffic originates from real end-users, but does not actually involve a true round-trip web query, and thus such traffic cannot download malware to an end-user device or expose personal information about and end-user.

The Intellyx Take

An IP proxy network is but one tool in the anti-fraud toolbelt to be sure, but they are good for more than fighting ad fraud – they also provide ad verification.

Today’s online advertising can be extraordinarily well-targeted. Because the IP proxy network can generate traffic from the devices of individuals who fall into any particular demographic, they can provide essential verification that the ad service bureau is serving ads to the people they should.

If they are not, then one possibility is fraud – or maybe simply a misconfiguration, or perhaps poor business practices. In any case, advertisers want to make sure their ad dollar is buying what it’s supposed to buy. IP proxy networks can provide that assurance.

Copyright © Intellyx LLC. Luminati is an Intellyx customer. Intellyx retains final editorial control of this article.