In my last Cortex newsletter I discussed the exponential growth pattern technology innovation always seems to follow, what Ray Kurzweil calls the law of accelerating returns.

I asked why such exponential patterns appear so ubiquitous – even extending beyond human endeavor to growth patterns in the natural world – and the answer was that groups of people are complex adaptive systems, and the self-organization of such systems can lead to the emergence of exponential growth patterns.

Armed with this exciting new perspective on rapid innovation, I headed to the International Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, hoping to see examples of such accelerating returns among the new products on display. To my dismay, such disruptive innovations were in short supply. Instead, the conference was chock full of repetition.

Take the home automation market, for example – one of particular interest as it’s an example of a market that takes advantage of the Internet of Things. True, there were a few innovations on display, but it seemed that dozens of vendors were sporting more or less the same technology innovations. The only exponential growth on display was the explosion of copycats, not the innovation itself.

Once again, I ask the question, why? Why do some innovations proceed exponentially, while others poke along, spawning copycats more than disruptions – even when the underlying technology leverages Moore’s Law and its corollaries?

And even more curious, why do product innovations rarely proceed along an exponential curve, even when their underlying technology does so?

Innovation Resonance

Innovation, of course, doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It takes buckets of money and even more importantly, the limited time of the innovators, who often bet their careers a particular idea will come to fruition. Both the investors as well as the scientists and engineers who do the work must thus have the will to invest their resources into developing the next innovation.

In addition, while some people think of “pure” research as an end in itself – where the good of science or humanity is reason enough to invest in such research – there’s no denying that a profit motivation is the primary driver (either directly or indirectly) for most such innovation.

True, there are always risks with disruptive innovation, and perhaps the more potentially disruptive, the greater the risk the work will lead to naught.

The most innovative organizations have the will to place bets on many lines of research, with the full understanding that perhaps most won’t lead to profit. The fact that some portion of such work will lead to innovations that will find plenty of market demand – and thus, profits – is good enough reason to cover the field with bets.

Market demand, in fact, is an essential element in the innovation equation. Current market demand, however, doesn’t drive the will to invest in disruptive product innovations, because the market doesn’t know it wants the innovative products that will result. Instead, such products drive market demand once they hit the market.

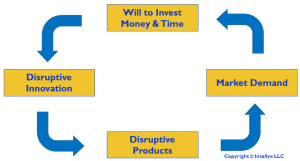

To illustrate how these forces interact, let’s put the reinforcing feedback loop that drives the exponential pattern of accelerating returns into the figure below.

In the figure above, disruptive products drive market demand, which in turn drives the will to invest in further innovations.

For the feedback loop to lead to exponential growth, there can be no mitigating factors that slow the loop down. In particular, investors and innovators must have sufficient reason to believe that there will be more than enough market demand for their innovations in order to invest all the money and time necessary in rolling out the next generation of technology.

Clearly, Moore’s Law and its corollaries work this way. Developing, say, the next generation computer chip is enormously expensive, both in terms of money as well as the time that researches must devote. If there were any question as to whether people would buy that faster chip, then the will to invest would drop, and with it the exponential growth pattern.

In other words, the loop above is tuned for maximum feedback. Using the metaphor of tuning here is no accident – you can think of the pattern above as an example of resonance.

Resonance happens when the elements in a system are tuned just so in order to feed back in an increasingly powerful way – whether it be an FM radio picking up faint radio signals at a particular frequency, or your microwave oven, carefully tuned to heat the water in your food by oscillating it at the resonant frequency of the H2O molecule.

Putting Brakes on the Exponential Express

Tuning the loop above means identifying disruptive innovations so likely to drive market demand that there’s no practical limit on the amount of will necessary to drive further innovation – a virtuous cycle to be sure, but not a cycle that always takes place, as my experience at CES drove home.

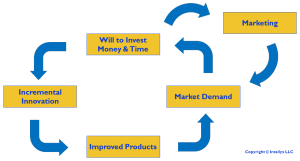

Just as your radio or guitar might easily be out of tune, so too might be your market innovation cycle, as the diagram below illustrates.

In the diagram above, investors don’t believe that innovation alone will drive market demand, so they decide to invest in marketing in order to increase such demand. But there are other fundamental differences between the second figure and the first, as none of the arrows in the market-driven innovation cycle above represent maximum tuning.

Investors hedge their bets, so only invest in incremental innovations. The resulting products are new and improved, but don’t disrupt markets. The market demand in such situations, therefore, is rarely due to the innovations alone.

While the first iPad was a disruptive innovation, driving its own demand, subsequent iPad models are examples of incremental innovation, even though they take advantage of disruptive technology advancements like increased processor speed. Sure, Apple is likely to sell more iPads because they are faster, but such an innovation is a product innovation (hence falling under marketing) more so than a technology innovation.

The second figure also explains what I saw at CES. Exhibiting at such a conference, of course, is a marketing expense, and the reason anybody wants to spend money on such folderol is in hopes of driving demand – for products that sport incremental improvements rather than disruptive innovations. If a vendor had a truly disruptive innovation, they wouldn’t need to bother with the tchotchkes and booth babes.

Tying Disruptive to Incremental Innovation

The two diagrams above are illustrations of opposite extremes of a spectrum. In reality, most innovations fall somewhere in between, and are thus a mix of the two models.

Take the Apple iPad, for example. We can agree it was a disruptive innovation, as it unquestionably disrupted both the laptop and smartphone markets, and rapidly established a market of its own.

And yet, did its success prompt the decision makers at Apple to spare absolutely no expense in rolling out the next version? Probably not – because they wouldn’t have had the comfort level that the iPad2 would be disruptive the way the first model was.

As a result, a disruptive innovation like the iPad might take a brief spin on the innovation resonance cycle, only to jump onto the more traditional, market-driven cycle for future versions.

Be that as it may, we still have innovation in our midst that continues on the resonance cycle for decades. Computer chips, data storage, computer memory, network speed, camera pixel density, and many other areas of innovation have shown remarkable persistence in their adherence to exponential growth.

Each generation of these technologies are disruptive in that they obsolete the previous generation, and also occasionally lead to disruptive products on the market like the iPad.

Clearly, such technology innovations were essential to the iPad’s success. After all, Apple tried its hand at the tablet market back in the early 1990s with the Newton Personal Digital Assistant, an ambitious but underpowered flop.

Today, exponentially advancing technology improvements in processor speed, memory, etc. are factoring into routine innovations in the iPad – but while the underlying technology innovations are disruptive, the incremental changes in the resulting products may not be.

The Intellyx Take: Where’s the Emergence?

The thrust of my previous Cortex was how the self-organization inherent in complex adaptive systems accounted for the exponential growth pattern we find in the innovation resonance pattern in the first figure above. Where in this article, then, are the emergent properties that result from self-organization?

We can find that self-organization in the will to invest money and time box. After all, there’s no hard and fast recipe for deciding when to invest in a potentially disruptive innovation. Furthermore, once the money is available, innovators must themselves take an inherently creative approach to rolling out the next generation of the technology in question.

If you take out your magnifying glass and spy on the various meetings that go into such decision making, you’ll see familiar human behavior – creativity, politics, arguments, risk taking, and many other elements of the human condition. You’ll never see emergence at that scale.

Only when you step back and observe the resulting patterns, however, emergence becomes apparent. Sometimes the innovation cycle hits its resonant frequency, while many times it does not.

For those patterns of innovation that do follow the law of accelerating returns, such patterns prove to be remarkably persistent. Such persistence is itself an emergent property of the loosely connected, self-organizing groups of people responsible for the day-to-day activities we call innovation.

Intellyx advises companies on their digital transformation initiatives and helps vendors communicate their agility stories. As of the time of writing, none of the organizations mentioned in this article are Intellyx customers.